Lois Faith Brumbaugh

20 years of missing you

A bright light went out the day we lost Lois.

Lois was my little sister. I will never get over it. I can remember staying with my Cripe cousins during the time she was being born. My father came over and the adults were having a discussion of what my baby sister’s name was going to be. Later, I remember going to my Grandma Weigold’s and seeing my mother with the baby next to her in the bassinet. Lois was a beautiful baby. She had dark hair and large brown-black expressive eyes.

I was always protective of Lois. Although I was five years older than she was, we would talk about life and things. She seemed to have the ability to attain what she wanted even with my parents. I would be in awe. In later life, I was always proud of her many accomplishments and abilities. I liked her sense of style, humor, piano playing, intelligence, and innate sensitivities. We weren’t very much alike but enough alike to “get life” in a similar way.

Let me tell you some about Lois.

God gifted her with a sharp mind and natural musical ability. She had perfect pitch and musical intelligence. If she could hear it, she could play it. Lois was quick with her wit making come-backs at just the right time. She also had a sensitivity toward people, noticing their moods or struggles. Her giftedness was appreciated by her colleagues, former college friends, close friends and acquaintances. Many shared with my family the ways she touched their lives, going the extra mile, or sharing a cup of coffee at the right time when they needed it.

Her bosses told us Lois could see something that nobody else noticed when interviewing a prospective employee. She would pick up on the little things that matter. She was a fun-to-be-around co-worker. Lois liked fashion. She made her own jewelry, wore dangling earrings, could put clothing together in a way that set the outfit off, sometimes sewing her own clothes. I liked watching her become a woman who overcame her shyness and learned to present herself well.

Lois was beautiful.

We share the brown eyes, they run in the family. Hers flashed brightly, intelligently. I loved Lois. The night I got the news that she had left us, it felt like I was walking in shock, like the world would never be quite the same, a similarity to the way the world felt when Princes Di’s crash was broadcast interrupting the evening’s programming, Dan Rather’s voice quivering in uncharacteristic emotion. Lois moved people that way. A person wanted her to succeed and do well, but we could see her vulnerabilities as well. I wanted my sister back, to talk to her again.

She had been my encourager, calling me up once in awhile and saying things that made me feel appreciated. Lois noticed those small things that others never commented on. She wanted to help my husband and me because she knew my family was going through a lot. My children and the other nieces and nephews thought she was the greatest. She always gave the “fun” quirky gifts at Christmas. They called her “Aunt Lou.” My oldest two remember her best. They were nine and eleven when she passed on.

The day we drove to Oregon to say our final goodbye was long.

I cried most of the way to Oregon. There were several vehicles with family members, cousins, my grandma, and others. While stopping at a rest area and viewing the river as it flowed, my young daughter, LaVonne, said to me, “I wish Aunt Lou was Sleeping Beauty and a handsome prince would kiss her and she would wake up.” We arrived in Stayton, Oregon, at Marilyn’s, my sister, house. Soon it was overflowing with people. Everyone was in disbelief and shock. We were devastated. My oldest son, Joshua, arranged the alphabet magnets on the refrigerator to read “Aunt Lou still loves us.” It was hard for my family to say good-bye to her. She was too young. Her death had come too soon and in an unnatural way.

The memorial service was full of tears and sadness.

When my brother, Paul, spoke he said, “It’s not right that we’re here today,” and he was right. My sister Juanita read this passage from the Word.

I pray that out of his glorious riches he may strengthen you with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith. And I pray that you, being rooted and established in love, may have power, together with all the Lord’s holy people, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge—that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God. Ephesians 3:16-19. NIV

Mrs. Odell, a former pastor’s wife, spoke of Lois in children’s church as a little girl, making eyes at Richey. We all laughed, imagining Lois as a little girl. At the end of her speaking. Mrs. Odell paused. Her eyes scanned the room, then she said with a confident voice, “God is still in control.” So much we needed to hear those words that day. The service concluded with all the verses of Amazing Grace being sung as we stood together. The voices raised loudly as one. There was energy in the air and power in the words. It felt as if we were claiming a victory over the darkness that had snatched my sister away.

One scene from that day is etched in my mind.

We are standing next to her fresh dug grave that is now her final resting place. The sod and dirt are slightly damp. We are on a hill there in Stayton, Oregon. Most of the mourners have left, but we remain. My siblings, Paul, Juanita, Marilyn, and me, are standing next to my father. We are all alone for a few minutes. My father’s long arms enclose us as we huddle together, heads bowed, unable to speak, sorrowing in solidarity through our broken hearts and flowing tears.

It is just the four of us and Dad.

Dad shakes his head and says he never thought something like this would happen in our family. We find ourselves agreeing, shaking our heads, overcome with a grief that takes your breath away and penetrates the inner core.

Then some of us wander over to baby Sharon Elisabeth Brammer’s marker, which tells of another sorrow, when the family grieved a few years before in 1982, when we lost my sister’s eleven month old to leukemia, the firstborn grandchild of my parents. I see the marker with her name. Fresh tears flow, and I feel the loss afresh. I am glad my sister is laid to rest near her niece. It seems right and fitting.

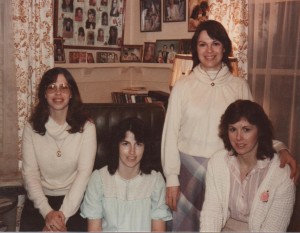

Sisters Forever, 1983: The Brumbaugh Girls at Grandma Weigold’s house: Norma, Marilyn, Juanita, and Lois.

This week it will be twenty years since we lost Lois.

I miss her and wish she was still here. Every once in a great while I will have a dream with her in it. She is vivacious and charming. I will ask her, “Why did you have to leave us?” and she will smile at me and then fade away. Then I wake up. It always makes me sad and happy mixed together.

For those of you who knew her, I want you to remember her smile and the gift she was to us. That is what we should think about at this time, the happy and loving memories of Lois Faith Brumbaugh, beloved daughter, sister, and friend.

First posted on meridianwoman.blogspot.com

ADDITIONAL LINKS

https://www.nlbrumbaugh.com/remembering-lois

Lois’ Song, I’m Thinking of You